There’s an interesting row going on at the moment about art, artists’ rights over their own work, parody, subversion of artwork, and all the rest of it. Right now it’s centering on two hefty sculptures which stand in New York’s financial district, Charging Bull and Fearless Girl. The creator of the bull, Arturo Di Modica, objects very strongly to the arrival of the second statue, which can really only be seen as a response to, subversion of and even a criticism of his own work. The best explanation of this story I have seen so far is by Greg Fallis, Whether or not Di Modia has a legal case probably remains to be seen, but it would be dumbfuckery indeed to try to argue that, because his sculpture supports capitalism, male values etc and Fearless Girl is all about the female empowerfulisation, he should just suck it up. (Read the Fallis piece. Properly.)

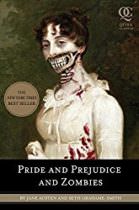

This is not to say it’s wrong for one artist to create something as a comment on, parody or or reaction against the work of another. Sometimes the new version is better than the original: there are certainly many writers who began their careers after reading a novel by someone else and saying to themselves, ‘For fuck’s sake, I could do better than that.’ It does, perhaps, get a little murkier when the new creation either couldn’t exist without the old, or cannot be understood if separated from it. You can cover your arse legally if you make sure that what you want to stamp your own pawprints on is out of copyright, like Seth Grahame Smith did when he came up with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. There are also certain legal exemptions and permissions with regard to using extracts of other people’s work or citing it as an inspiration for a parody – or a rebuttal – but if you base your own stuff on someone else’s special thing, you shouldn’t be too surprised if they object. They have every right not to like what you have done if your interpretation is the polar opposite to their worldview.

This is not to say it’s wrong for one artist to create something as a comment on, parody or or reaction against the work of another. Sometimes the new version is better than the original: there are certainly many writers who began their careers after reading a novel by someone else and saying to themselves, ‘For fuck’s sake, I could do better than that.’ It does, perhaps, get a little murkier when the new creation either couldn’t exist without the old, or cannot be understood if separated from it. You can cover your arse legally if you make sure that what you want to stamp your own pawprints on is out of copyright, like Seth Grahame Smith did when he came up with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. There are also certain legal exemptions and permissions with regard to using extracts of other people’s work or citing it as an inspiration for a parody – or a rebuttal – but if you base your own stuff on someone else’s special thing, you shouldn’t be too surprised if they object. They have every right not to like what you have done if your interpretation is the polar opposite to their worldview.

You can’t ensure that people percieve your work the way you intended it, of course: the Manic Street Preachers had to resign themselves to audiences bellowing the chorus to Design For Life in entirely unironic delight rather than appreciating it as a searing critique of emotional inarticulacy and shit. But we should all be wary of assuming that the art which sits best with our own worldview is the one with the greater moral right to exist unchallenged.